Two of the most common words used to assess the quality of a movement observed in a sport or the gym are form and control. I like to think of form as the optimal technique and mechanics of a movement, and control as the ability to execute those mechanics properly. Being able to perform a movement with form and control is to say that you have mastered that movement.

When describing control, many fitness experts look to motor control: the process by which the nervous system stimulates the muscles and allows them to fire, contract, and move the skeleton. I prefer a more pragmatic approach that I call movement control: the understanding, practice, and development of motor control as seen in complete human movement. In other words, movement control is the ability to maintain form and control throughout the full range of motion and across different time and load demands. Movement control is the mechanical or physical result of motor control.

You can use this simpler definition of control to understand, measure, and train movement ability. Since movement control is grounded in motor control, I will first describe a simplified picture of the nervous system and then discuss movement control by observing a basic body shape such as standing. Following this blog post will be articles related to addressing the hollow body position and the plank.

Summary of the Nervous System

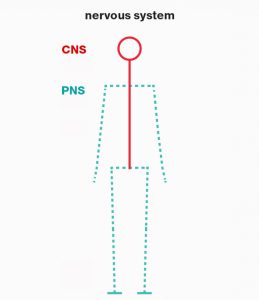

Movement involves a complex coordination of signals flowing through your nervous system, sometimes processed by your brain, and physical or mechanical actions in the musculoskeletal system. While it can be complicated, I find that it’s necessary to have a basic understanding of the nervous system in order to discuss movement control. Movement control can be thought of as a two-sided system: one side is the central nervous system (CNS), the brain and spinal cord, and the other is the peripheral nervous system (PNS), the projections that innervate all muscle tissue. This mode (as seen in figure 1) helps us understand that there are mechanical actions that we want to be as limitless as possible, and then there is the processing and networking (CNS) side that we need to be as stable as possible.

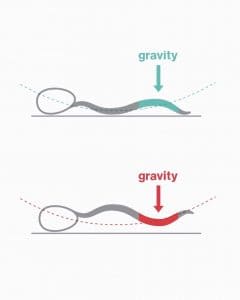

Given the conflicting demands placed on the nervous system, I see the spine as a mediator between these two sides. Thecurvature of the spine (as seen in figure 2) seems to have naturally adapted over thousands of years of human evolution to allow us to move at different levels of the spine. Human spinal composition allows for head movement, arm movement, and rotation to name a few examples. Most important, the spine moves to accommodate maintaining connections throughout the PNS, while still protecting and stabilizing the CNS. Although the spine is an extremely complex system composed of bones, soft tissue, and many other things, we are going to eliminate all those variables and think of it as a simple rod called the midline.

This simplified understanding of the nervous system as a two-sided system with a rod that balances the CNS’ need for stability and the PNS’ need for mobility allows us to approach and challenge movement control through basic shapes.

Basic Shapes

I like to introduce movement control by using fundamental shapes that the human body needs to have with respect to global position and orientation in space. These shapes are fundamental because they seem to be required for every movement you may need to do. I take these shapes and challenge them in ways that allow you to develop the movement control that is crucial for the proper execution of the movements throughout my book, Freestyle. First, I introduce standing as our starting point for movement based on human evolution. Next, I introduce the hollow body position which adds a change of orientation in space (lying on the ground). This change of orientation requires using muscular tension to control the shape of the spine. This tension is the beginning of developing the control of our global position throughout movement. Finally, we flip the body around to a prone (face down) position and continue to develop muscular tension to control the spinal shape using a different strategy.

Standing

One of the first things a gymnast learns is their training is how to stand. They stand tall with legs straight, chest up, back flat, belly tight, feet together, and arms to the sides. My gymnastics team started every session this way, standing in formation to be told what to expect for the session. This is also how we finished each session. This simple act of standing was a way of establishing form and power from the beginning of the session and no matter how beat we were at the end, we had to finish strong. You may not think much about the act of standing, but standing dictates and influences movement control. You can observe a body standing tall at spinal level and see how the position of the spine affects the movements that follow. As a retired gymnast who now focuses on strength and conditioning, I have come to realize that the utility of the gym is that it exaggerates reality. This exaggeration applies to everything, even standing.

Standing Point of Performance

-

Figure 3 Stand tall with your feet together, both heels and big toes touching.

- Lock out your knees, squeeze your butt, squeeze your belly, lift your chest, and pull your shoulders back.

- Lengthen your neck by imagining a string being pulled from the top of your head, and tuck in your chin without looking down.

- With your arms straight and your hands by your hips, turn your thumbs out so that your palms are facing forward.

If you think about the anatomical stance that you might see on a poster at the doctor’s office (as seen in figure 3), it is a position of strength and control. It is strong because the spine is stacked up vertically from the ground and in a position that it is the most stable. This stability exists thanks to the surrounding musculature, such as the back muscles pulling in toward the spine to keep the shoulders back and down. The butt is also tucked in, leveling the pelvis. The abs are engaged to create an imaginary protective belt around the lower back. This standing position is relatively easy to adopt, and with practice you can transfer it to many movements.

As a strength and conditioning coach, I encourage a lot of change in spinal position with control which begins by practicing simple and static shapes. Your spine needs to be protected and set up to send the necessary signals to facilitate optimal movement. This is where the fitness community’s obsession with core strength and midline stability comes in to the picture. A very basic way to challenge these two things is to learn how to keep your spine in the most neutral first, stable position possible—the anatomical or stacked spine described earlier.

Even though you spend most of your day upright, whether you are standing or seated, your spine changes orientation in space every time you move. It leans forward, back, and side to side, as well as combinations of those. These changes of orientation in space create different stressors on your spine due to changes in muscular tension around the spine and, most important, to the orientation of your spine in relation to the pull of gravity (as seen in figure 4). Moving while keeping your spine in this neutral or anatomical position gives you feedback for understanding what movement control is and how it relates to common concepts in the fitness industry, such as core strength and midline stability.

It is my belief that by observing, describing, and practicing standing as a skill, which requires an understanding of form and also control, we can carry over to all other aspects of one’s performance. Fitness doesn’t need to be complicated, it can start with something as simple as chasing excellence in a basic physical expression such as standing.

For more information you can reference Freestyle the book, Page 52, Chapter 2, Part 1.

Watch this video on motor control and an introduction to the hollow body.

Contributor: Carl Paoli